How “Midstream Bivalence” Leads to Reckless Philosophy

In philosophy, we all love the idea of discovering a new powerful argument, or finding a formidable refutation, or figuring out a beautiful new articulation, or validating our preconceived beliefs. We crave something confident & conclusive. And so any bug that both provides that confidence and slips past even very intelligent people is going to turn up everywhere.

Here’s one of them.

“Midstream bivalence” is a nickname for the following:

- Several premises along a syllogism enjoy large confidence but not total confidence,

and - Those premises are treated bivalently (shoehorned into either “true” or “false”),

and - When deciding whether to count those premises as “true” or “false,” we choose to “round up” that large confidence (but not total confidence) to “true.”

Those of us who have done data analysis know that these sorts of “rounding errors,” when buried within a process, are notorious for the bad and/or overconfident conclusions they can yield. But it takes some experience and/or examples to see the issue intuitively.

A syllogistic conclusion is a conjunction of all of its premises. Consider some logic within a spy story featuring 3 independent agents:

- A: Larry is on our side.

- B: Julie is on our side.

- C: Kris is on our side.

- D: Anyone on our side will fire their flare when the signal is sent.

- E: Thus, upon sending the signal, all three of Larry, Julie, and Kris will fire their flares.

This can be expressed as A&B&C&D→E.

Let’s say we’re all largely confident in each of A, B, C, and D independently. And so, we “round up” to “true” on each. This gives us T&T&T&T→T. Nice!

But… is this “okay”? It feels kind of sloppy, but it can’t be that bad, right?

Well…

… turns out it’s bad.

There are independent chances, albeit small, that each of Larry, Julie, and Kris might be double agents. Let’s say a 10% chance each.

Furthermore, there’s a chance that the agent may miss the signal for whatever reason — incapacitated, asleep, distracted, etc. Let’s say that chance is 10%… but note that it’s an independent possibility for each agent.

Now things look more like this:

- A: Larry is on our side. (P=0.9)

- B: Julie is on our side. (P=0.9)

- C: Kris is on our side. (P=0.9)

- D: If Larry is on our side, he will fire his flare when the signal is sent (P=0.9).

- E: If Julie is on our side, she will fire her flare when the signal is sent (P=0.9).

- F: If Kris is on our side, she will fire her flare when the signal is sent (P=0.9).

- G: Thus, upon sending the signal, all three of Larry, Julie, and Kris will fire their flares.

Now, if we “round up” to P=1 on each premise, then our final conclusion is P=1 as well.

But what if we refuse to “round up”? Well, any single one of the 6 premises makes the conclusion false. The way we account for the growing epistemic space of possible failure is by multiplying those probabilities together:

0.9*0.9*0.9*0.9*0.9*0.9=0.53(?!)

Oh dear.

Now what looked like a sure bet has become a coinflip.

That’s a big difference!

That’s a big… problem.

Check out the quick 5m video below for more about the scope of this problem and how it drives some of the most notorious, endless conversations in philosophy:

Bonus

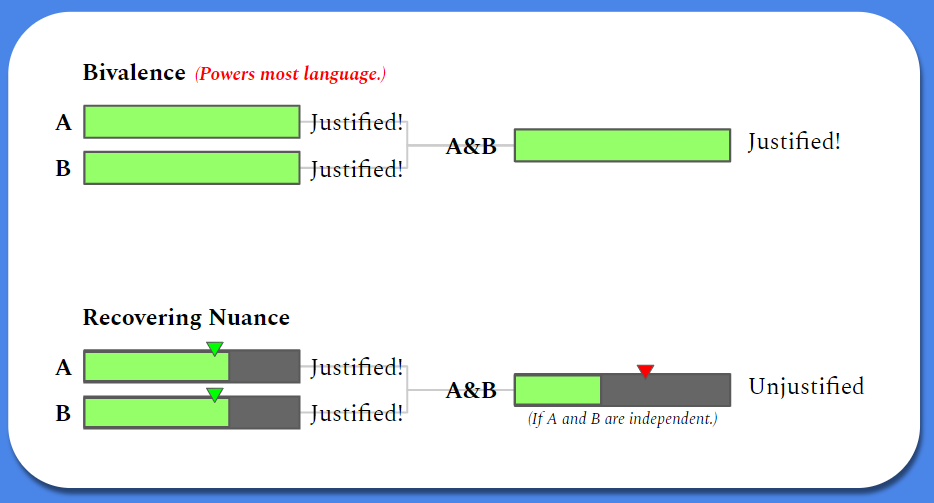

Here’s a quick diagram that quickly illustrates how, even if we define our threshold of confidence for “justification” (to “cash out” in a bivalent way), the practice of bivalent “rounding” midstream can make the difference between calling something justified or unjustified:

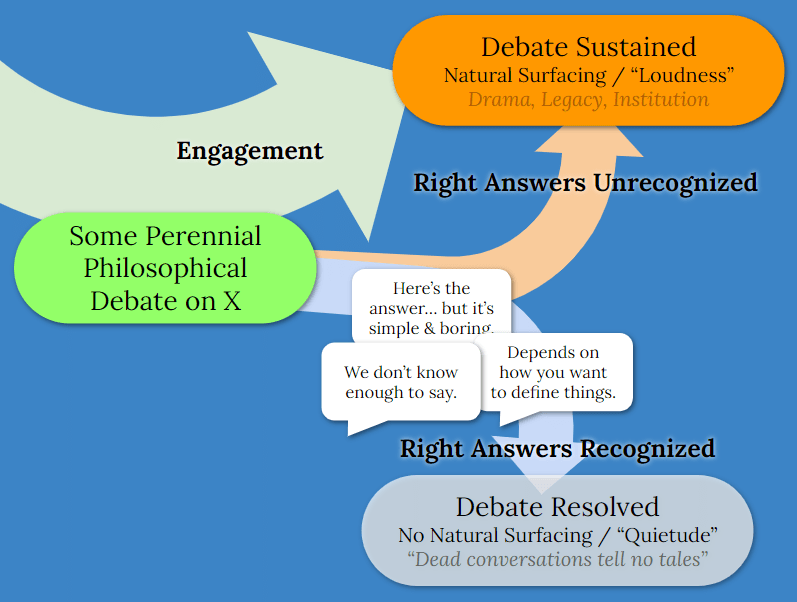

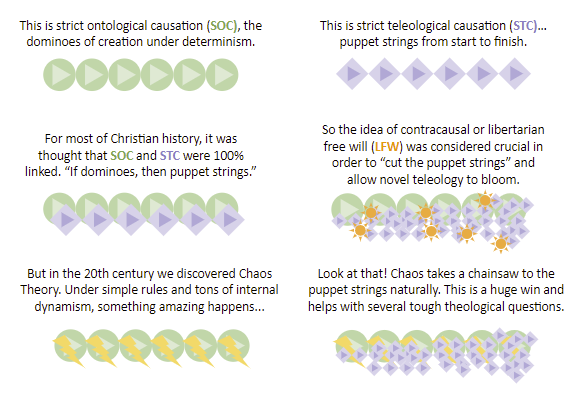

And here’s a diagram that illustrates the issue discussed in the back half of the video — selection pressures “reward” bold conclusions and obscure the fact that we already have the answers to most of the hottest (historically, and continually) philosophical debates: Usually these answers are, “It depends on how you want to define the terms,” and, “We don’t know and probably can’t know.”

These right answers are boring, they can’t be capitalized, and they end conversations. These three nails in the memetic coffin help explain philosophy’s problem with heuristic capture (in short, those whose careers & names are wholly invested in there being “more to it” cannot be trusted when they say “there’s more to it,” despite them being genuinely honest, intelligent, respectable, and endorsed by their peers — heuristics we like to lean on).

Are Actual Loops of Objects Impossible?

Horace, Irene, and Julia are discussing what kinds of numbers and arrangements of objects are actually possible.

Horace comes up with a thought experiment with the following premise:

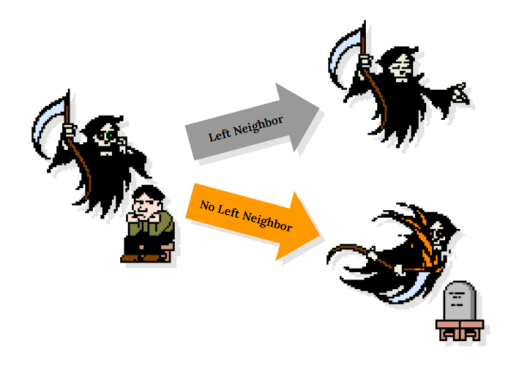

- The Doomed Man is alive and surrounded by a loop of Grim Reapers. It is the Grim Reapers’ job to kill any Doomed Man — and they enjoy doing it!

- Whenever a Grim Reaper sees the Doomed Man alive, it says to the one on its left, as a manner of courtesy, “After you,” deferring the task and closing its eyes. If there is no Grim Reaper on its left to which to defer, it does the deed itself.

- Whenever a Grim Reaper is told, “After you,” it says to the one on its left, as a manner of courtesy, “After you,” deferring the task and closing its eyes. If there is no Grim Reaper on its left to which to defer, it does the deed itself.

- Soon enough, the Doomed Man has been slain by one or more Grim Reapers.

It’s clear to all three friends that this situation is logically impossible. This is because even though each premise of the setup is conceivable individually, their combination is something both non-completable (via the endless deferrals from #3) and yet somehow complete per #4.

Horace concludes that the problem is found in #1: They are arranged in an actual loop.

The most elegant solution, he argues, is to instead arrange them in a queue, with a firm start and end. Once #1 is altered in this way, then each other conceivable premise can occur, and that’s nice, because it bothers us when we’re told a perfectly conceivable thing cannot occur for what seem like ephemeral reasons.

His conclusion: Actual loops of objects are impossible. (You may feel this is a strange takeaway.)

Irene, however, points out that we’re still in a pickle. That’s because an alternative #3 is perfectly conceivable: That the Grim Reapers have a manner that, if they lack a Grim Reaper on their left, they will instead defer to a Grim Reaper on their right (if there is one). Instead of an endlessly cyclic deferral, you get an endlessly zig-zagging deferral.

Her conclusion: Actual loops of objects are impossible and actual queues of objects are impossible, too. These must be theoretical only. (You may feel this is also a strange takeaway.)

Julia shakes her head.

Actual loops of objects are fine, Julia says. So are actual queues. Even actual infinities of objects are okay! The problem, Julia explains, arises when the Grim Reapers are infinitely deferential and yet #4 states the Doomed Man has been slain by one or more.

Now this doesn’t mean, clarifies Julia, that Grim Reapers cannot defer at all. If you have infinite Grim Reapers in a sequence who, while deferential, upon being deferred-to always do the deed themselves (vs. deferring a second time), then after a brief moment of courtesy the Doomed Man shall be slain.

Julia’s right. The root problem is not the number or arrangement of actual things after all.

Rather, the root problem is any scenario that stipulates that an endless job has come to an end.

Any locally-finite job is completable — at least, completable for magical beings we imagine — as long as that means genuinely locally-finite, lacking any dependencies upon the total number of objects sneaking into the job’s parameters.

You can have an actually endless racetrack in the real world. Just take the cross-cutting lines — the “ends” — off of a normal running track. But it’s not fair to ask someone to complete a race upon it, now robbed of its finish line. Which is to say that while the phrase, “The Running Man has finished the race,” is conceivable in isolation, its pairing with our end-deprived track is not.

Horace is predictably eager, upon hearing that, to blame the circularity of our track. He says to snap and stretch it into a straight course.

Irene is still concerned; what if the rules of the race are such that when you reach the ends, you have to turn around and go back the other way?

Julia sighs, and we know why: Whether the track is circular, straight and ended, or infinitely long, you can do a 100-meter dash. It’s all about the task “on top” of the actual objects, and whether or not you’ve defined it to be impossible.

More Info

In the below video from Joseph Schmid’s “Majesty of Reason” channel, Dr. Alex Malpass discusses this kind of “unsatisfiable pairing,” an observation which elegantly solves a number of stumpers, from the Grim Reaper Paradox to Thomson’s Lamp Paradox to Benardete’s Paradox of the Gods. While different folks have different takeaways from these and similar paradoxes, some use them to suggest that actual infinities are impossible (which in turn insinuates a First Cause) much as Horace used his bespoke Circle of Grim Reapers paradox to assert that actual loops of objects are impossible.

A Stupid Electoral System for Goofs

(Or, “How to Keep a Republic.”)

Election methods may seem a bit off-topic for this blog, but it couldn’t be more appropriate.

It’s a contemporary American story, and it starts with systems, flows into memetics, and finally has things to say about morality and culture, including the state of American Christianity as popularly portrayed.

Stick with me here. Each step is crucial.

Part I: Anchovy Pizza

Yes, anchovy pizza.

… Hey, I said stick with me! Your rewards will be great: You’ll soon know the 3 Clues of a Wrong Winner.

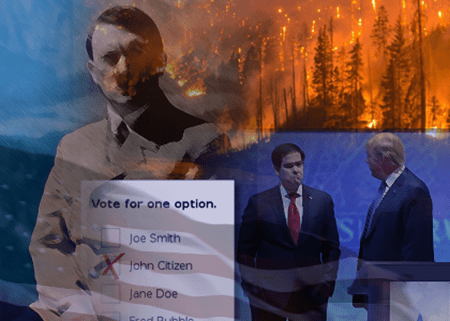

Imagine there are 5 people at a party, enough money for 1 pizza, and 4 pizza choices — cheese, pepperoni, veggie, and anchovy.

3 of the people despise anchovy pizza.

2 of the people love — absolutely adore — anchovy pizza and spurn anything else when anchovy is in play.

They want the pizza choice to represent the group. Their pizza should be like a strong republic — an expression of the “will of the people” that serves those same people and their preferences.

So what method do they use to gather group preference?

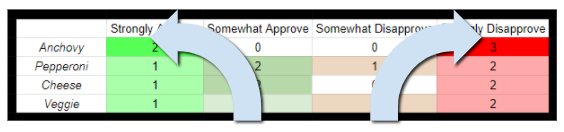

They could use Approval Vote, where each person gives “thumbs up” and “thumbs down” to each option. The pizza with the highest number of “thumbs up” wins.

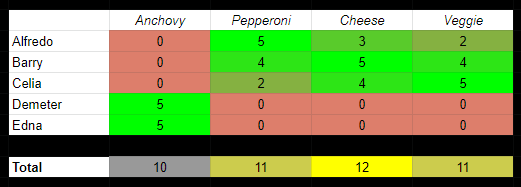

Here, Cheese pizza is the winner, with 3 thumbs up.

Or, they could use Score/Range Vote, where each person gives a score to each option (here, 0 to 5). This is what we in the game development industry normally rely on for audience tests.

Again, Cheese pizza is the winner, with a score of 12. This also gives the clearest picture of where preferences fall, and in this case provides us with a powerful intuitive sense of which pizza certainly shouldn’t win (Anchovy).

Unfortunately, these 5 folks did not use the above methods.

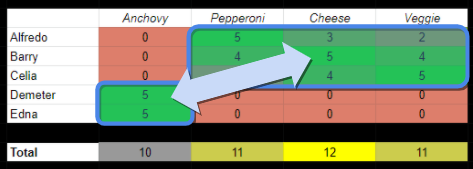

Instead they decided to use Plurality Vote, where you mark only your very favorite option and are robbed of the ability to express anything else.

And now Anchovy pizza wins. Pretty awful, eh?

So… what happened? Well, when robbed of the ability to express anything except which choice is your very favorite, the anti-Anchovy majority got split up.

This is called, appropriately enough, “splitting the vote.”

And it’s not a joke.

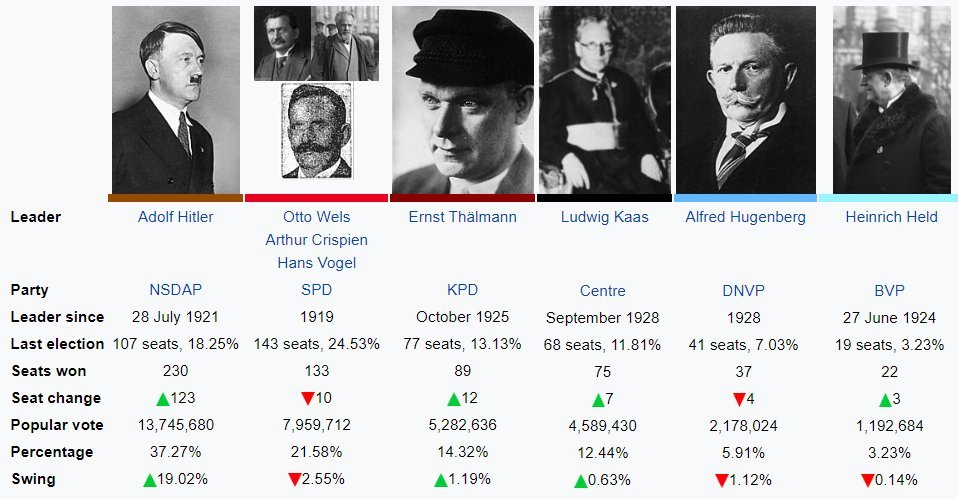

In the July 1932 German federal election, Anchovy Hitler and the Nazi Party acquired a plurality of seats in the Reichstag for the first time. The use of “mark only your favorite,” combined with the number of choices involved, meant that, for all we know, the results did not express popular will in the least.

Think about it. The percentages above are not measures of popular will; they are measures of sizes of blocs of favorites. The Reichstag was apportioned according to sizes of blocs of favorites. This is stupid. A stupid system for goofs. A system simply itching to give power to the next Anchovian pied piper that comes along.

The Nazis didn’t win a majority that July — they never won a majority prior to banning the other parties — but it kicked the snowball down the slope. Emboldened by their results, they ramped up violent terrorism and increased pressure against their political rivals. A multi-way power-struggle ensued throughout the remainder of 1932, with would-be dictator Franz von Papen grasping to advance his own Machiavellian ambitions, culminating in a final, desperate re-coalition that handed the German government to the Nazis the next January. In March 1933, another election increased their seat dominance — again, leaning on the artificial advantage that Plurality Vote gives to extremists. Soon after, they passed the Enabling Act, eviscerating what separation of powers remained.

The core issue is the following stupid problem: When “mark only your favorite” is used, the sway of ideological groups is effectively divided by the number of choices in that group. Those variables should never affect one another; but here, they do. It’s as if they’re grafted together “upside-down,” since mainstream views tend to have a greater number of candidates representing them.

When this happens, the vote-splitting is given the name “spoiler effect.”

Therefore, one Clue that suggests a Wrong Winner (“Someone who won under Plurality Vote but is a bad representative of the group, i.e., would lose a head-to-head match-up vs. another candidate”) is when there’s a clear “cohort split” across ideological groups or personal loyalties (following “pied pipers”). We can call this the “Pied Piper” Clue.

But this data is sometimes hard to come by, since individual preferences can get “averaged out” in reports.

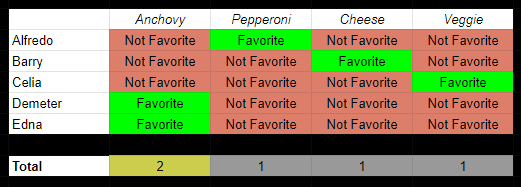

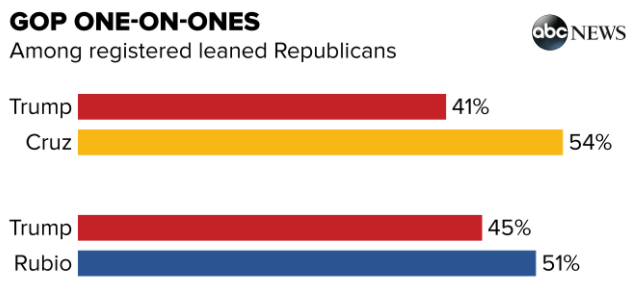

Another Clue that suggests a Wrong Winner is when the winner is uniquely polarizing or controversial, which can be measured using approval ratings.

Even though Demeter and Edna abhor the non-Anchovy options, they are unable to make the non-Anchovy options look controversial because there simply aren’t as many of them influencing the tally.

This Clue, which we’ll call the “Controversial Character” Clue, paints the following picture:

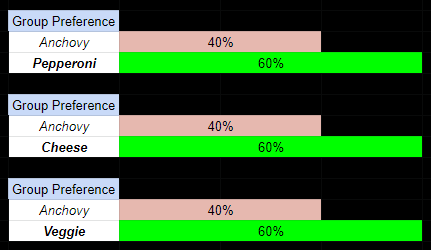

The final Clue that suggests a Wrong Winner is if, in head-to-head match-ups, or “duels,” the so-called “winner” loses most often, or even every time.

Notice what dueling does: It corrects for Plurality Vote’s devastating problem (breaking completely with more than 2 options available) by limiting the vote to 2 options only:

We’ll call that the “Duel Loser” Clue.

To recap, that’s:

- “Pied Piper” Clue. (An ideological cohort split or fringe personality.)

- “Controversial Character” Clue. (Remarkably more polarizing than others.)

- “Duel Loser” Clue. (He’s actually quite the loser, when we correct for Plurality Vote’s stupid nonsense.)

And now let’s apply these to something more contemporary: The 2016 Republican Presidential Nomination.

The Republican Primaries and Caucuses of 2016 were hotly contested between candidates Donald Trump, Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio, and to a lesser extent (but still relevant) John Kasich and Ben Carson.

After March 1st’s “Super Tuesday,” 15 of the contests were over. Trump had won 337 delegates to Cruz’s 235, Rubio’s 112, Kasich’s 27, and Carson’s 8. Trump had also won 10 states vs. Cruz’s 4 and Rubio’s 1.

But every contest was either using pure Purality Vote or using a system that involved Plurality Vote at one or more stages (which is also corrupting).

Like in Germany in July 1932, the results were not necessarily measures of popular will, but of sizes of blocs of favorites.

According to the systems at play, Trump was winning after Super Tuesday. However, at this point, Trump may have been a Wrong Winner. This is a devastating possibility because Wrong Winners do not look like the losers they are. As such they gain the momentum, the loyalty, and the solidarity. (Remember when your NeverTrump uncle morphed into a Trump apologist? I certainly do.)

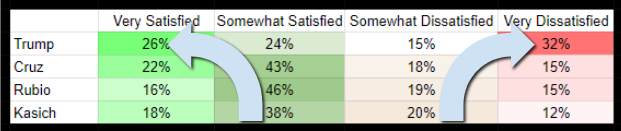

On March 8, one week after Super Tuesday, Langer Research Associates released a poll of Republicans and Republican-leaning voters. The researchers asked a variety of questions, and was deep enough to go “under” superficial and corrupt Plurality-style polling.

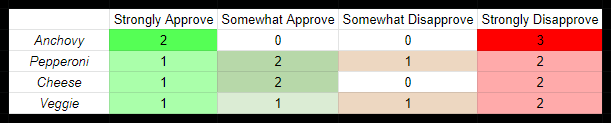

This study showed that Donald Trump was a “Controversial Character” in the sense defined before:

But, most horrifyingly, it showed that Donald Trump was a two-fold “Duel Loser”:

What a loser!

So how on Earth was he winning? Smells fishy, right?

Fishy… like an anchovy!

This is exactly the kind of ideological and/or personality-driven cohort split that makes Plurality Vote so screwed up when there are more than 2 choices on deck.

Through the Podesta e-mail leaks, we discovered that a year prior, the Clinton campaign understood that fringe candidates like Donald Trump, if legitimized, could “force all Republican candidates to lock themselves into extreme conservative positions” in order to maintain a coalition between Republican-leaning independents and the Far Right. “The variety of candidates is a positive here… we don’t want to marginalize the more extreme candidates, but make them more ‘Pied Piper’ candidates… we need to be elevating the Pied Piper candidates so that they are leaders of the pack and tell the press to [take] them seriously.”

In other words, the campaign saw that it was to their advantage to use their influence with the media to elevate Donald Trump. And when Trump became the nominee, they were pleased as punch.

But it’s important to note that Donald Trump never had a majority result until June 2016, with his big, expected win in New York. Back in March 2016, the other candidates knew what was happening, but refused to ally into an anti-Trump coalition — even as Trump averaged a 40% vote shortfall vs. the combined vote count of his strongest 2 opponents in each race.

The nonpartisan electoral reform organization FairVote, which advocates Ranked Choice Vote (another fine system), also knew what was happening: “The GOP split vote problem continues,” they wrote on March 8, 2016. “Its use of a plurality voting system may well allow a candidate to win the nomination who would be unlikely to win in a head-to-head contest with his strongest opponent.”

In other words… the Wrong Winner!

After Rubio dropped out after his disappointing result in Florida, the Cruz and Kasich campaigns called one another “spoilers.” It wasn’t until a month later that Cruz and Kasich finally set their differences aside, as their delegate shortfall grew and grew, and as Trump continued to feed off of Plurality Vote‘s toxic sewage and mutate out of control.

Cruz and Kasich came up with a “noncompete” plan so that they could stop spoiling one another, divide a few first-place wins among themselves, and push Trump into a series of second-place finishes.

Ultimately, it was the only math that could lead to a contested convention.

But it was too late.

Part II: Avoiding Anchovies

The only way to stop a Wrong Winner is to:

- Coalition in order to circumvent Plurality Vote‘s unacceptable, atrocious vote-splitting effect, and

- do so early enough so that the Wrong Winner hasn’t already captured the support and enthusiasm of the group, enchanted by his pseudo-crown, that is, the powerful — but wrong — signal that this is truly the group’s favorite.

The mainstream Republicans failed to coalition early enough to stop Donald Trump, a Wrong Winner if there ever was one, from securing the nomination. He never should have been the Republican Party candidate, and needless to say, did not represent the GOP’s platform and stated principles.

Because Plurality Vote takes a chaos-chainsaw to candidates when there are 3 or more in play, decisionmakers (whether party insiders, campaign strategists, or voters) — if they are rational decisionmakers — will do what they can to control the chaos:

- Party insiders will try to elevate somebody early, around which they can rally the masses into a united coalition.

- Campaign strategists will recommend “take-down” tactics against candidates with the biggest “my favorite!” bloc, and against candidates that share values and may be acting as direct “spoilers.”

- Voters will desperately try to stop their buddies from voting third party, since voting third party under Plurality Vote is about as helpful as eating your own ballot. Many of us intuitively sense the rational need to coalition under Plurality.

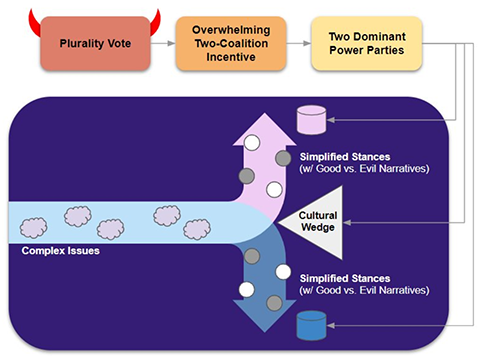

And this is why the United States is a Two Party regime.

It’s not a Two Party system; the system is Plurality Vote, which drives and sustains Two Party dominance precisely because there is no plausible, incremental way to rationally-decide our way out of it.

Put another way, to “avoid anchovies,” there is an overwhelming incentive to coalition tighter and tighter until there are only 2 choices left, because that’s the only circumstance in which Plurality Vote is fine. Failures to do this result in chaos and anti-republic results, and increase the chance of fascist and extremist cult-like personalities coming to power.

Part III: Inflame & Divide

Once there are only two viable parties left, a new overwhelming incentive emerges: Any issue that could be politicized “should” be.

With the right messaging, incoming complicated issues can be framed within a narrative in which your party is the hero and the other party is the villain — or where your party is “like us,” and the other party is “not like us.”

The leaked copy of Frank Luntz’s 2006 “The New American Lexicon” shows how neoconservatives like Luntz had been using such methods since the early 1990s to “hook” these political memeplexes into our deepest fears, hopes, and loyalties.

That messaging is “spin.” And that framing is “shoehorning.” They require dishonesty about the complexities of these issues and they require persuasive hyperbole about the “other side.”

But it’s undeniable, and irresistible. The worse the other guys look, the better you’ll do, because there are only two viable parties. Every complicated issue is “untamed land” to conquer, study, prepare, sow politicization, and reap polarization.

And the result?

Pew Research Center

Now, remember how I just used the word “irresistible?” It is mistaken to think that we can solve this problem by collectively changing our minds and deciding to come together as a country. And yet that’s how our American polarization problem is framed again and again.

If we go back one step, we notice similar “it’s our fault” framing whenever we’re stuck deciding between two candidates for President that we’re not satisfied with. “If everyone voted third party,” we hear incessantly, “we wouldn’t have to settle!”

But as we saw, Plurality Vote does not reliably produce correct winners, and the more viable candidates there are (like via third party groundswells), the more random chaos it causes.

That’s why we’re stuck in this Two Party regime.

We’re locked in it.

Part IV: Culture Power

Most of us aren’t aware that Plurality Vote gives us Wrong Winners. We assume that the system in place isn’t abysmal; we assume that the system is “good enough” that our vote “trickles up” with fidelity, and won’t betray us.

As such, we see our vote as a morally-significant expression of support.

Since we’re rationally locked-in to one of the Two Parties, we tend to rationalize those expressions of support that we give. We hitch our wagons, and our reputations, to what these “teams” are doing. It affects how we think, how we talk, how we behave, and how we socialize.

Of course, you don’t have to be a Party loyalist.

Plenty of principled libertarians can barely stomach the GOP.

Avowed leftists vote for Democrats only begrudgingly.

But the less reliable we are as Party supporters, the less the Two Parties care about us. Why grovel to purists when it’s the central terrain that’s actively contested, especially those indecisive, low-information folks who can be won-over by scaremongering and wordplay?

The Two Parties especially can’t afford to waste their energy on high-information ideological purists whose interests straddle the Party platforms. Not only are they unreliable — “disloyal” — but they can’t be won-over through clever marketing.

Who does that sound like?

That sounds to me like moderate Christians: Mainline Protestants, American Catholics, and American Orthodox.

White Evangelicals, by contrast, get lots of attention. For whatever reasons — and those reasons are myriad, really, and go back decades — white Evangelicals are reliable Republican Party loyalists.

Their strong alignment with one of the Two Parties means there’s a network of strong incentives to “boost” them, both from the Republican Party itself and from entertainment/news media profiting off of the sports-like “Civil War” narrative. So you hear from their leaders, you see them being interviewed, and when the media wants “The Christian Perspective” from “The Christian Worldview,” a white Evangelical appears on screen.

But what if they’re the “Wrong Winner” when it comes to representing Christians in the United States? They’re only 25% of Americans; Mainline Protestants, Catholics, and Orthodox combine for 35%. Notice a “Plurality Problem”?

Remember that the pseudo-crown of Wrong Winner sends a powerful — but wrong — signal that this is truly the best representative.

And, of course, this is to say nothing for the liberals and concerned conservatives whose voices within the white Evangelical cohort are tougher to hear.

For 4 years we’ve heard folks baffled that “American Christians” so openly abdicated even a pretense of moral authority in their thralldom to such a clownish, depraved political leader. The solution to the puzzle is those quotation marks at the beginning of the paragraph. The real sample of American Christians is as split as anyone else, grumbling every election cycle about the need for a third way along with the inability to muster one.

Part V: The Meaning of a Vote

Deja vu warning. (And thank you for bearing with me; you’re almost done.)

Most of us aren’t aware that Plurality Vote gives us Wrong Winners. We assume that the system in place isn’t abysmal; we assume that the system is “good enough” that our vote “trickles up” with fidelity, and won’t betray us.

As such, we see our vote as a morally-significant expression of support.

But Plurality Vote does give us Wrong Winners. The system in place is abysmal; the system is not “good enough” that our vote “trickles up” with fidelity. It can definitely betray us.

As such, we should not see our vote as a morally-significant expression of support.

Instead, it is only a helpful exertion of power, contributing to the primary mission of making sure the worst viable candidate loses.

The breakdown:

- Under fine systems, like Score/Range Vote or Ranked Choice Vote, our vote is a morally-significant expression of support.

- Under Plurality Vote, our vote is only a helpful exertion of power against the biggest threat.

Yes, the meaning of your vote just got trashed. That’s a lame meaning. It’s certainly not what we were taught.

But don’t kill the messenger.

Kill Plurality Vote.

And don’t vote like it’s gone until it’s gone.

Addendum

The politicization of ecological science is threatening the future quality of life of our children and grandchildren. This isn’t alarmism. It’s just an alarm.

We are the stewards of our families, our homes, the land we live on, the air we breathe, the water we drink, and the systems we maintain for the good of our neighbors around the planet. It’s “on us.”

And yet, there may be no plausible way to take rational action with Plurality Vote standing in the way. This is already inexplicably part of the “Culture War.” There’s only one way forward. Use your time, money, and voice to fight for electoral reform, at a local level and nationwide.

Sharing this is a good first step. Please take more steps, too.

Resources:

- The Equal Vote Coalition, advocating Score/Range Voting (S.T.A.R. method).

- FairVote, advocating Ranked Choice Voting.

- American RCV electoral reform efforts and successes thus far.

Plurality Vote won’t go away until we end it. Notice the “red” hidden within our elections. Tell others. Fight the good fight.

Potentially Bad Philosophy

Quietude might be described as as figuring out under what odd conditions it might be good to question some of our most trustworthy guides in philosophy and theology.

This is dangerous stuff, because we depend on those guides. We rely on their investment of (life)time, their investment of contentious discourse, and we take advantage of their brainpower. We stand on their shoulders. So when we choose to hop off their shoulders (or more commonly, hop onto another giant’s shoulders), we’d better have a good reason.

After we invest our trust in a person, concept (meme), or family of concepts (memeplex), it’s tough to make us leave. The speedbump we felt on the way “in” grows into a wall against going back “out.”

The feeling there is “incredulity.” As Manowar‘s 1987 heavy metal song “Carry On” claims, “100,000 riders! We can’t all be wrong!”

To keep incredulity in check, we ask, “When might even 100,000 heavy metal fans be wrong?” or more to the point, “When might dozens of brilliant philosophers be relying on fundamentally poor metaphysics?” What memetic “forces” could entrap even the otherwise trustworthy? When should we row against the current?

Viral Wildcards

We talked before about logical Wildcards. Any concept that has “vivid ambiguity” can be used, deliberately or not, to “bridge-make” (jump to conclusions that don’t really follow) and “bridge-break” (make legitimate conclusions seem like they don’t follow).

But this doesn’t just happen in isolated moments and stop there. Anything “useful” can stick and spread. This includes “Monkey’s Paw useful,” granting immediate wishes at a hidden, horrifying downstream cost.

Furthermore, that downstream cost may be “confusion, and the chatter it causes.” While we’d call this a “cost” in terms of what we consider praiseworthy and constructive, it is not a memetic cost, it is a memetic benefit.

That’s because this chatter boosts surfacing. It’s hard to hear Quiet folks.

The rhetorical utility of vivid ambiguity, combined with its natural self-surfacing, becomes a Wildcard-fueled memetic engine:

A Potential Problem

An example of the above pattern may be the philosophical concept of Aristotelian potentiality.

I’ve said before that I don’t think it’s possible to confront Wildcards directly (see the bottom-right gray box, above). All we can do is consider alternatives and try them on for size. Last time we did this with metaethics. Today it’s potentiality.

We read in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

“… Another key Aristotelian distinction [is] that between potentiality (dunamis) and actuality (entelecheia or energeia)… a dunamis in this sense is not a thing’s power to produce a change but rather its capacity to be in a different and more completed state. Aristotle thinks that potentiality so understood is indefinable, claiming that the general idea can be grasped from a consideration of cases. Actuality is to potentiality, Aristotle tells us, as ‘someone waking is to someone sleeping, as someone seeing is to a sighted person with his eyes closed, as that which has been shaped out of some matter is to the matter from which it has been shaped.’

This last illustration is particularly illuminating. Consider, for example, a piece of wood, which can be carved or shaped into a table or into a bowl. In Aristotle’s terminology, the wood has (at least) two different potentialities, since it is potentially a table and also potentially a bowl.”

(I’m not going to summarize the above so you’ll have to read it.)

This Aristotelian perspective, whereby potentiality in a sense ‘lives’ within an object, is widespread in classical Christian theology and reverberates even in modern modal analytic philosophy. But I suspect it may just be a poor (but intuitive!) way of expressing prospective imagination. I’ll show you what I mean, and why the Aristotelian sense doesn’t fit nicely with a couple examples (which in turn expose the inconsistency of the language games we play).

I can look at a quarry and imagine the potential of building a cathedral using its stone. But if we allow the test of “potential or not” to include every other requirement for cathedral assembly (including laborers to work the quarry and adequate incentives to motivate them), then it doesn’t seem so natural to say that some rock formation has such potential, in isolation. It needs help. Reductively, nothing happens unless the universe helps, including all prior states of the universe up to that point, in a cosmic help-funnel of “efficacious Grace” concluding at that final capstone. This is not simply universal reliance on some Unmoved Mover; this is, “potentiality is not real.”

In other words, in a universe empty of sculptors, but replete with rocks, no rock has potential to be sculpted. It is only when we grant the antecedent “but if there were sculptors” that its potential suddenly “is there.”

This is not real stuff. Rather, potentiality is simply a roundabout, yet shorthand way of conjoining a fact or object X with a set of antecedents, imaginary or not, which as a group are sufficient for some consequent Y. And then we utter, “X has the potential for Y.”

Aristotelian Potentiality’s Payoff

Whenever widespread language and intuitive conceptualization is imprecise in this way, we’d expect a sensible explanation for it — a rational reason why the irrational description has memetic resilience and virulence (sticky and spready).

The answer is that we’re very sub-omniscient. We don’t know very many of the facts “God knows,” so to speak. And we therefore treat the unknowns as “possible worlds,” leaning on the “holodecks of our imaginations” to narrow the focus of our prospect-seeking. This helps us avoid the anxiety of “analysis paralysis,” which is handy because, of course, the early bird gets the worm.

It should be noted that well-developed spatiotemporal faculties may be a prerequisite for using this “visual” approach to handling evaluation of contingency and consistency given uncertainty. Some studies suggest that children with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder, while just as capable as others in handling counterfactuals, take different strategies to evaluate them, preferring lists of facts and their contingent relationships vs. “holodeck stories.” However, as they age they acquire skill in both.

Aristotelian Potentiality’s Discomfiture

One way to expose the irrealism of Aristotelian potential is to apply it to that which is real and closed, and find it doing conflicting things; examples where it clearly “ain’t right.”

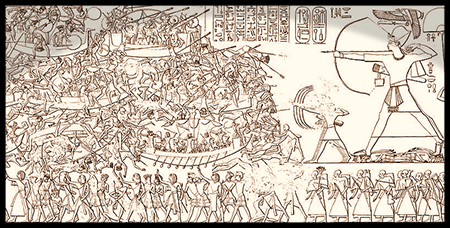

“Sea Peoples Potential”

Consider the sentence, “The Sea Peoples who invaded Egypt in the 12th century B.C. could’ve been Aegeans.” We say “could’ve” here when we know the answer is fixed, but simply unknown. And therefore there’s a sense of “potentiality” even when it’s obvious the Sea Peoples have already come and gone, and were who-they-were.

“Fallen Coin Potential”

Another example is, “The coin could‘ve landed tails, but it landed heads.” We say “could’ve” here, and retrospectively invoke the sense of potentiality we felt 5 seconds ago, prior to the flip, when the result was unknown, and therefore probabilistic. We say this even though the result of the flip was deterministic, the fixed result of chunky kinetic forces* we humans have trouble tracking.

Put another way: “Deterministic results couldn’t be other than what they were; so why/when do we give them probabilities anyway? How on Earth do we get away with saying both ‘couldn’t’ and ‘could’ve’ about them?” These questions now have simple answers.

* (If needed, imagine the coin flip in a virtual simulated environment, to control for “quantum” or “free will” factors.)

Conclusion

I affirm the finding of a number of early 20th century philosophers that metaphysics comes down to language. It’s often buggy. These bugs sometimes foster tiny, sneaky non sequiturs that let astounding conclusions pop forth. Unless trained against these, even brilliant people are more likely to shout “Eureka!” than “Error!”

This phenomenon creates a memetic incentive to unknowingly exploit, and tendency to inherit, buggy metaphysical concepts (because we trust tradition and the brilliant, renowned people who pass it along). I suspect Aristotelian potentiality is such a thing.

Further Reading

- To explore how open language is compatible with a closed past, present, and future, read “Schrödinger’s Cup: A Closed Future of Possibilities.”

All Metaethics in Brief

It’s been over 3 years since I last posted on this blog! Where on Earth have I been?!

First, having two children is a lot harder than just one. Second, my career has become quite a bit more demanding. Third, it was hard to think of more things to say without repeating myself, and I’m happy with the amount of airtime my existing posts have been getting.

From this and direct feedback, it’s apparent that folks appreciate quiet theology. It doesn’t skyrocket YouTube hits from dramatic confrontations and rebuttals. But perhaps it accomplishes something a little better.

A while ago I made a “clip show” post that summed up my views on libertarian free will. The time has now come to make a “clip show” post on metaethics. Brazenly I assert that all metaethics can be captured in brief.

Let’s see if you agree.

- Morality is subjective in one way and objective in two ways (“SOO“). It is subjective in that it always proceeds from the interests and preferences of persons (or Persons, like God). It is objective in that there are statements about those interests that are factual (such that I could lie about them). It is also objective in that the way to optimize those interests is a strategic question with correct and incorrect answers. Any search for “ultimate objective value” is doomed to failure.

break - Ignoring or “failing to mention” the subjective component makes commands more effective. We parents learn this very quickly. It catches the listener flatfooted and often roots the imperative in what feels immovable and irresistible. In other words, there is memetic fitness in using moral language that ignores the “S” in #1. We then trick ourselves into thinking that the “SOO” framework is bad, because it fails to capture the moral language with which we’re familiar, and which proves so effective on us and others! But this is only because our familiarity has a utile error embedded in it, into which we’re inculcated from a very young age.

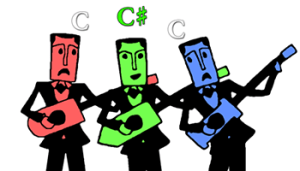

break - Per the 2nd “O” in #1, we tend to think consequentially. But since we’re not omniscient — in fact, we’re rather poor at anticipating all the meaningful consequences of our actions — heuristics can be helpful. While heuristics always come with certain risks, they can also give us powerful shortcuts and social cohesion. Here we distilled it into three “moral musicians”: Red (rules), green (clumsy goal-seeking), and blue (intuition). The article includes a breakdown of “minority reporting” showing that, schematically, this is indeed all a consequential system.

The above 3 observations adequately explain the existence of any metaethical position you please. In other words, take any moral theory, and you can explain it in the above terms.

This is a significant discovery if true. Right now we’re simply proposing it and trying it on for size. To do so, if you’re interested in more details about the above observations, follow the links inside to the deeper explanations. Then, put it to the test: Think of a moral theory, and see if it can be explained by the above 3 observations. A more fiery way to frame it: Try to think of a moral theory that cannot be elegantly explained by them.

Addendum for Christian readers:

These observations are also consonant with Scripture, which has a “social interest exchange” view of morality that repeatedly puts it in monetary language (covenants, debit, credit, obligation/owing, justice in merchant’s scales terms, etc.) that is alien to the purely objective moral realism of the Hellenic schools.

“Heed God” doesn’t come from him weirdly entailing some Platonic abstract. “Heed God” comes from his being Creator (so we owe him everything), Father (so he has our best interests at heart), and Judge (so he’ll eventually bring everything to account).

“Fatherhood” (so-defined) theoretically cancels out subjective impasses, like canceling out terms in math, leaving us with objective normativity in terms of our own good (remember your mom saying, “This is for your own good”?). And therefore, “at the end of the day,” nothing much changes; “during the day,” however, we enjoy a solution to the Euthyphro Dilemma that doesn’t involve (as much) special pleading.

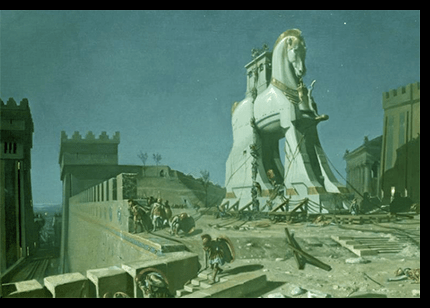

The Ontological Argument’s Trojan Horse

The Ontological Argument for God has always been controversial. Some believers think it works. Other believers say it does not. I am in the latter group.

It’s good to explore when and if arguments for God are dysfunctional.

I am indeed asserting that the Ontological Argument does not work. It’s tricky, though, because OA’s power is in its incoherence, and incoherent things are like ghosts (through which swords of coherence impotently pass).

As the above linked article from the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy remarks, “This helps to explain why ontological arguments have fascinated philosophers for almost a thousand years.”

The following is a new rhetorical attempt at exposing why it’s bad.

Here’s something that looks sort of like the Ontological Argument. I’ll call it the “’Idea-About-an-Ontological-Thing’ Argument.”

- The idea of God is that of that which a greater thing cannot be conceived.

- Existent things are greater than nonexistent things.

- It follows from 1 and 2, therefore, that the idea of God is that of a being that exists (whether or not he really does; somebody can say that this idea corresponds to something that really does exist, and someone else can deny that).

The above is true, but it doesn’t tell us anything about what really exists (or not). Everything is properly “cloistered” in a discussion about ideas.

Now, here’s a trick of language.

Consider these two statements:

- (A): The idea of God is that of that which a greater thing thing cannot be conceived.

- (B): God is that of which a greater thing cannot be conceived.

Notice the difference? (A) says “The idea of” at the front. And yet, when paired, these statements basically mean the same thing to us.

They’re both “bluish.”

We drop “the idea of” in (B) for brevity, but we understand that it’s still just a hypothetical, especially in the context of (A) — that is, “Hey, we’re just talkin’ ideas here, definitions.”

Now consider these two statements:

- (B): God is that of which a greater thing cannot be conceived.

- (C): God is, in actuality, that of which a greater thing cannot be conceived.

When paired, these two statements also basically mean the same thing to us.

They’re both “olivish” — they’re ontologically affirmative.

Of course, the unbeliever would reject (C) because that’s the point in question.

So, how do you make subtly make an ontological affirmation while making it look like innocent, “Hey, we’re just talkin’ definitions?”

You use (B) as a Trojan Horse… a logical wildcard. It acts one way one moment, and another way another moment, because it is ambiguous.

If the OA’s first premise = (A), then you get “’Idea-About-an-Ontological-Thing’ Argument.” Inert and useless!

If the OA’s first premise = (C), then the unbeliever — very rightly — complains about a begged question. Fallacious!

By using (B), you get the innocence of (A) and the affirmative power of (C).

That is, since OA’s first premise = (B), it looks like a mere hypothetical that suddenly, somehow materializes.

That is exactly how OA feels, and this is why.

Conclusion

The Ontological Argument is not cogent, but its bugs are subtle.

Kant dealt with the problem elegantly when he said, “Existence is not a predicate,” but isolating the Trojan Horse may be more vivid for some folks.

There are other problems with OA, like “‘Greatness’ requires a referent,” but the above should do.

Addendum

Modal Ontological Arguments might, at first, seem stronger than the more classical formulations, but they just use a different kind of ambiguity to make their “hop”: Using Rule S5 to squish “redundant” modal operators together that actually have different modal scopes (and thus aren’t actually redundant and squishable). Modal scope fallacies famously foster Trojan Horsesque conjuration.

Use epistemic modality to “lead-line your lab.” Here, the scopes of modal operators are easier to intuitively track, and it becomes more obvious when a string of operators should not be collapsed together (when they have different scopes).

Please Stop Saying Free Will Contradicts Universal Reconciliation

There’s a meme that universal reconciliation (wherein the Gehenna of Judgment doesn’t last forever) doesn’t work with free will (or agency, or dignity, or cooperation, or what have you).

We’ve discussed this before on this blog, but that material had some distractions that I hope we can avoid this time around.

The point this time is to focus, and make a really simple rebuttal of the idea that these two things are incompatible.

In order to focus, we’re going to avoid defining free will — whether you think it’s the libertarian kind, or a compatibilistic kind, or something else, should be unimportant to the argument.

(The argument is pointing out a non sequitur — “Free will’s falsity is not a corollary of purgatorial universal reconciliation, and PUR’s falsity is not a corollary of free will” — by way of a thought experiment.)

The Three Humans

Imagine that there are only 3 humans: John, George, and Ringo.

Here are 3 possibilities:

- In possibility 1, only John shall freely submit to God at Judgment, and George/Ringo shall remain in rebellion.

– - In possibility 2, both John and George shall freely submit to God at Judgment, but Ringo shall remain in rebellion.

– - In possibility 3, all three of John, George, and Ringo shall freely submit to God at Judgment.

We don’t have to commit to any of these possibilities, but can talk about a series of “ifs” related to possibility 3.

In other words, let’s “float” possibility 3 for a moment, and see what happens:

- If possibility 3 happens, there’s no contradiction between possibility 3 and free will, since all three humans in the group freely submitted.

– - Furthermore, if God knows that possibility 3 shall come about, there still shouldn’t be any contradiction with free will.

- (God knowing something does not have any effect on the group’s free will.)

–

- (God knowing something does not have any effect on the group’s free will.)

- Furthermore, if God inspires a writer to assert that possibility 3 shall come about, there still shouldn’t be any contradiction with free will.

- (God inspiring a writer to make that assertion does not offend the group’s free will.)

–

- (God inspiring a writer to make that assertion does not offend the group’s free will.)

- Furthermore, if folks read those assertions and subsequently believe with confidence that possibility 3 shall come about, there still shouldn’t be any contradiction with free will.

- (Folks holding to a conveyed foretelling with confidence does not offend the group’s free will.)

All done.

All across the board, John, George, and Ringo’s free wills have not been offended in any way, even if possibility 3 is held true for the sake of argument. This hypothetical premise simply isn’t catastrophic to freedom, dignity, agency, and whatnot. Everything’s fine.

Conclusion

PUR may be false. Perhaps some will refuse to submit at Judgment, and opt for interminable rebellion instead.

But the truth or falsity of PUR is not presently at issue.

Rather, at issue is the meme, “PUR would contradict free will if it were true.”

And that meme is false. It entails non sequiturs.

Incredulity

How can it be that the above meme is so virulent and resilient, even among very educated, sincere, brilliant thinkers?

The reason is because non sequiturs are extremely difficult to root-out, especially when they involve tough-to-crack concepts like free will.

I suspect that a modal scope fallacy is responsible for this non sequitur. Modal scope fallacies are very, very easy to commit, even from people vastly more intelligent than you or me.

Visit the Purgatorial Hell FAQ and search the page for “free will” to look deeper into the modal scope fallacy we often see here.

But He is Also Just: The Simplicity & Complexity of Biblical Justice

The Bible talks about justice a lot.

In the abstract, Biblical justice is really straightforward. But the manner in which Biblical justice plays out is complicated.

That’s because justice — that is, “equitable recompense for behavior” — is not just about “following rules,” as if rules are the basis of all moral decisionmaking.

Rather, things like rules and deals and deserts (what is “deserved”) are strategies under a purpose-driven plan.

That is to say, these things are very useful, which is why we see them used. But they’re not “home runs” every time.

Equity(s)

Imagine that your child misbehaves. There are many different ways you could respond in equity to that infraction.

- You could pull them aside and give them a time out.

- You could take away a privilege for a while.

- You could threaten to take away access to some future event.

- (And more.)

Each of these might be, individually, equitable to the infraction. They’re not so excessive that they feel arbitrary and give your child anxiety issues. But they’re not so light that they affect no change of behavior. Not too hot; not too cold; just right.

Notice that equity is defined according to purpose on both ends.

So, which method should you apply?

Let’s look at more purposes to help answer that question.

Earlier, you told your children that if they misbehaved this morning, they would lose access to video games. You “laid down a law.”

It makes a ton of sense to go by that law, even though you have several equitable responses before you.

- First, it feels less arbitrary because it seems “objective” (even though you came up with the law yourself). This is great, because objective references feel both stable (less anxiety) and immovable (less “b-b-but!” push-back).

– - Second, it’s an effective display of your seriousness; it teaches your children that you make good on your warnings.

Boom! Two more purpose-driven considerations.

But there may be even more purpose-driven considerations, depending on the circumstance.

- Was your earlier law tailored as a general broadcast to all of your children, but may not be best-suited to the child who ended up disobeying?

Ouch. That one’s not so easy.

- Is the disobedient child now showing genuine remorse and proof of regret? Should you reduce the punishment? To what degree (remember, the other kids are watching)?

– - Let’s say they’re not showing regret; is positive punishment even helpful in this particular instance? Would positive punishment only incite resentment, due to the child (as she currently is) and the circumstance (as it is)? If you took a self-sacrificial approach — bearing the burden of the infraction in a different but compelling way — would you powerfully evoke empathy? Would that prove to be better in terms of purpose?

Notice that with each of these questions, you’re considering something other than equitable recompense — in the familiar sense — for the infraction. (You’re considering violating a previous law in the first, you’re considering mercy and forgiveness in the second, and, in the third, you’re volunteering for injustice to provoke a needed change of heart from a hardened person.)

And why are we considering these things?

For purpose.

Purpose is — in the moral hierarchy — supreme.

That is, justice (“equitable recompense for behavior”) is

- tailored to purposes when many responses would qualify as equitable, and

- can even bow-the-knee entirely to purposes, when purposes demand.

Sedeq & Mispat

As we see above, what starts out looking relatively simple — “equitable recompense” — is very soon complicated by the supremacy of purposes, leading to all sorts of twists, turns, and surprises.

This is what makes the topic complicated in Scripture, even though Biblical justice has a clear definition in the abstract.

First, we have the concept of Heb. sedeq — what is correct and true, especially according to expectations between people, and between people and God.

Leviticus 19:36a

“You shall have sedeq balances, sedeq weights, your ‘ephah’ (a unit of dry measure) shall be sedeq, and your ‘hin’ (a unit of liquid measure) shall be sedeq.”

(There are numerous verses along the same lines.)

Second, we have the concept of Heb. mispat — which is an administered judgment with overtones of sedeq (and especially when it’s God’s judgment).

Job 34:10-12 (Elihu, speaking on God’s behalf)

“Therefore, listen to me, you men of understanding. Far be it from God to do wickedness, and from the Almighty to do wrong. For He pays a man according to his work, and makes him find it according to his way. Surely, God will not act wickedly, and the Almighty will not pervert mispat.”

Scripture explodes with vivid articulations of mispat, and how mispat is perverted: Through equity (sedeq) failures.

(The concepts are not synonymous, but so interrelated that they are paired together dozens and dozens of times.)

Sometimes these failures are due to favoritism, like preferring one person over another with no warrant.

Leviticus 19:15

“You shall do no iniquity in mispat; you shall not be partial to the poor nor defer to the great, but you are to judge your neighbor with sedeq.”

Other failures can be through excess or recklessness.

For example, Abraham appealed to God not to destroy Sodom because of collateral damage against some hypothetical number of good people — and how this would violate mispat.

Genesis 18:25

“Far be it from You to do such a thing, to slay the righteous with the wicked, so that the righteous and the wicked are treated alike. Far be it from You! Shall not the Judge of all the earth do mispat?”

God’s mispat Judgment, of course, will be sedeq — that is, it will not be a show of favoritism, and will not be excessive.

Psalm 96:13

“Let all creation rejoice before the Lord! For He comes, He comes to judge the earth. He will judge the world in sedeq, and the people with His faithfulness.”

Aph

Third, we have Heb. aph — furious anger, fuming through the nostrils, often described as “kindled” and “burning.” (There are other “flavors of wrath” as well, but we’ll focus on aph here.)

And here’s where it gets complicated.

We know that aph and mispat/sedeq can be expressed simultaneously — God’s “just wrath.”

Consider Eliphaz’s ranting, false claim that Job’s children must have sinned to cause their deaths:

Job 4:7-9

“Remember now, who ever perished being innocent? Or where were the upright destroyed? According to what I have seen, those who plow iniquity and those who sow trouble harvest it. By the breath of God they perish, and by the blast of His aph they come to an end.”

Eliphaz’s buddy Bildad backs him up:

Job 8:3-4

“Does God pervert what is mispat? Does the Almighty pervert sedeq? When your children sinned against Him, He sent them away for their sin.”

(When Job stands his ground, insisting that these misfortunes were not sedeq, Bildad retreats to a catch-all — ‘all people are terrible’ (Job 26:4-6), so whatever suffering befalls them is legit. Job correctly responds that this is less-than-useless; “catch-all depravity theodicy” would make God’s mispat meaningless.)

But when Elihu — speaking on behalf of God — comes on the scene, he throws a curveball, and interrupts the bickering with a fresh, revelatory picture of God’s ways. (More about Elihu.)

Elihu agrees that God’s aph brings punishment to the wicked (Job 35:15), but rightly insists that God’s loftiness makes our sins less injurious against God, not more (Job 35:6, 8).

God may express aph, but:

Job 36:5

“God is mighty but despises no one; he is mighty, and firm in purpose.”

Let that sink in for a moment.

And this isn’t the only place we see this. In Scripture, mispat/sedeq are frequently portrayed as something “less intense” than aph, even subduing or metering aph in service of purpose and productivity.

Psalm 6:1

“Lord, do not rebuke me in your aph or discipline me in your hot displeasure. Have mercy on me, Lord, for I am faint; heal me, Lord, for my bones are in agony.”

Jeremiah 10:24

“Discipline me, Lord, but only in mispat — not in your aph, or you will reduce me to nothing.”

Notice that? Mispat for a set of infractions is explicitly juxtaposed against an excessive (beyond mispat) reaction of “ceasing to be.” You can say it’s aph to obliterate somebody for any amount of sin, but you cannot say it is mispat.

Mispat and aph don’t seem like unconditional pals anymore, do they?

Jeremiah 30:11

“‘I am with you and will save you,’ declares the Lord. ‘Though I completely destroy all the nations among which I scatter you, I will not completely destroy you. I will discipline you but only in mispat; I will not let you go entirely unpunished.'”

Jeremiah 46:28

“‘Do not be afraid, Jacob my servant, for I am with you,’ declares the Lord. ‘Though I completely destroy all the nations among which I scatter you, I will not completely destroy you. I will discipline you but only in mispat; I will not let you go entirely unpunished.'”

Here again we see that a mispat reaction — a “Biblical justice” reaction — is tailored to specific infractions.

Boolean extremes need not apply at the court of mispat.

But how can this be? Is this a contradiction? How can mispat/sedeq and aph play nicely together one moment, but mispat/sedeq be defined against aph the next?

Scripture supplies the answer: His aph lasts only for a moment (Psalm 30:5).

(We ought to have suspected something like this, since “time & circumstances” can break such apparent contradictions.)

In Scripture, God’s looming wrath is conveyed through all sorts of vivid, and often frightening, and sometimes humorous, illustrations:

- Broken bones

- Total obliteration (no corpse; all memory wiped out)

- Slaughter (corpse; memory remains, in shame)

- Incineration

- Weapons disarmed

- Exposed loins

- (Etc.)

But his purposes remain supreme. Any aph “only for a moment” shall not override God’s expressed “as surely as I live” interests.

Implications for Eschatology

In discussions about the nature of God’s Judgment and the Second Death, it’s really common to see folks come to the table with assumptions that act as “filters” on Scriptural imagery.

Indeed, which “road” you take at the multi-pronged eschatological “fork” is largely about buying into one set of stipulations and/or heuristics over another. Anybody who’s spent time and self-critical honesty in the nitty-gritty knows that there’s no proposal that fits “cleanly”; each proposal, if it is coherent, must relax some things and treat other things at full, face-value force.

Scripture ain’t simple on this topic. Period. Anyone who says otherwise is kidding themselves (or trying to sell you their book).

But formal logic can serve as referee.

As long as we keep our philosophy “quiet” — doggedly resisting the temptations of utile ambiguity — we can derive powerful corollaries from bold Scriptural assertions like:

- God is abounding in love and mercy.

- God doesn’t ultimately despise anyone, but is firm in purpose (as such there may be ancillary disfavor, e.g., Rom. chs. 9-11).

- Mispat and sedeq are often “less than aph.”

- God’s aph lasts only for a moment.

- Even mispat and sedeq are subordinate to God’s purposes; the King can see fit to forgive debts, reinstate debts, and tailor the forms of equitable recompense to suit his plans (Matthew 18:21-35).

- God makes the sinner listen to correction.

- God’s arm is never too short.

- God’s practice of mispat and sedeq is upon and from a throne established in love.

And these bold assertions, and their direct corollaries, point to a particular set of eschatological stipulations/heuristics — one of the “big three” early Christian teachings on Judgment — as a forthright and powerful compass.

Conclusion

You’ve heard this hand-waving chestnut before: “God is loving, sure. But, he is also just.”

When do folks typically say this?

They typically say this when they want to rationalize a proposal that is otherwise plainly suboptimal in terms of God’s stated “as surely as I live” interests.

This only “flies” if Biblical justice is an ambiguous logical wildcard that rationalizes any old punishment at all.

The real complexity of Biblical justice — when the straightforward definition collides with purpose-driven nitty-gritty — often makes people think they can get away with this.

But mispat tells a different story.

Determinism Doesn’t Mean a Micromanaging God

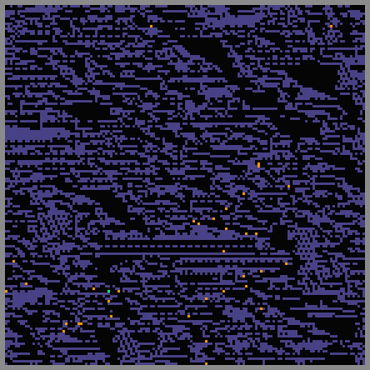

“Durdle Dwarves” is a simulation where little “Dwarf” pixels dig-through and build rock-like structures. They do this according to a set of 20 rules. A rule tests a Dwarf’s vicinity and provides a response. (For example, if a Dwarf notices a drop-off to his left, he’ll build a new piece of “bridge”; that’s 1 rule of the 20.)

The simulation is 100% deterministic, and the state of the world at a certain time is a strict function of those initial rules, plus the starting state.

For instance, this starting state:

Yields this world state after 13,500 ticks:

Let’s pretend we don’t like something about this result. Perhaps that structure just below the middle — the one that looks a bit like a road with a lane divider — displeases us.

We could just pause the simulation and erase it, of course.

Because we have the arbitrary power to change things at any time, you and I are sovereign over this world.

But each interruption like this comes at a cost. Even though we were displeased by the road-like shape, we’re also displeased to intrude upon the natural flow of events. In our set of innate interests, one interest is that the world have as few of these intrusions as feasible.

Another option is to change the starting state of the world. Let’s make our initial two “Adam & Eve Dwarves” one block farther apart.

And here’s what things look like after 13,500 ticks:

Hooray! We got rid of that nasty road-like pattern.

But there was a cost here, too. The world is dramatically different now. Here’s the “Before & After”:

This kind of thing is nicknamed the “Butterfly Effect” in chaos theory. The tiniest of changes, over time, produces explosive world differences in nonlinear and/or interactive systems.

This is irritating, too, because we liked the world basically how it was, we just didn’t like the road pattern. Now everything is way, way different.

How annoying!

Let’s define micromanagement as, “Controlling things with surgical precision.” Is there a way to micromanage-away that road, so that we keep the rest (through our precise surgery), but also without using the blunt force of the eraser?

You might be thinking, “Why don’t we alter the starting rules, so that the road never appears?”

Unfortunately, merely altering one of the 20 core rules, or adding just a few rules, has the same explosive “Butterfly Effect” that dramatically changes the world state at frame 13,500. So, this would fail to micromanage.

As it turns out, the only way to pull this off is to have tons and tons and tons of core rules.

And this, of course, has the cost of being horribly ugly and inelegant.

Some folks would tolerate that inelegance. But you and I agree that this basically defeats the point of creating these guys at all. We take pleasure — let’s say — in the emergence of these forms out of an elegant, simple foundation.

Where This Leaves Us

“Durdle Dwarves” is just a computer program.

However, it’s such an obvious deterministic cloister that it serves as the “worst case” for verifying whether determinism always means full micromanagement.

The answer? It doesn’t.

If we have an innate interest in maintaining systemic elegance, then the degree to which the world is micromanaged is equal to the degree to which we have found it warranted, in certain rare circumstances, to intrude, even as we’d rather not intrude.

Notice that our innate interests have what’s called “circumstantial incommensurability” at the “13,500 circumstance.”

It’s not power-weakness that makes a wholly-satisfying solution impossible. Remember, we’re 100% powerful over that world.

Rather, a wholly-satisfying solution is arithmetic nonsense.

What This Shows Us

An entity can be 100% sovereign and powerful over an interactive deterministic world, including that world’s core rules, starting state, and modifications to any subsequent state.

But if that entity has innate interests in an elegant ruleset, then the world is not necessarily micromanaged. Then, if the entity never intrudes, then the world is not micromanaged at all. And if the entity intrudes to some limited degree, then the world is micromanaged only to that degree.

Primary Causation & Secondary Causation

If we start with an elegant core ruleset in a sizeable interactive system, then as time goes on, I will lose surgical control over that system, even if I’m 100% sovereign over it.

True, but pretty dang counterintuitive.

It is only when I find it justifiable to intrude that I can wrest-back some amount of surgical control, temporarily.

- The reductive perspective is that since these decisions are all “up to me,” everything in the system reduces to “my causation.”

–

This is the perspective from which St. Irenaeus wrote in the 2nd century, “The will and the energy of God is the effective and foreseeing cause of every time and place and age, and of every nature.”

But this fails to capture something important to me, doesn’t it? Indeed, a formative perspective is needed to capture my interests.

- The formative perspective is that there is a meaningful — according to my interests — difference between primary causation, the stuff that glows brightly with my exceptional exertions of power, and secondary causation, the “teleologically-dimmer” stuff that starts to act weirder and weirder as time goes on.

–

This is the perspective whereby we rightly deny that God “authors” sin under chaotic determinism; rather, he broadly suffers it.

These two perspectives are simultaneously true in heterophroneo (a concept we’ve been exploring on this site that’s similar to Aristotle’s hylomorphism, but not exactly).

Conclusions

- Those who say “under determinism, primary and secondary causation have no meaningful distinction” are mistaken.

– - Those who say “under determinism, a sovereign entity has 100% micromanagement, irrespective of that entity’s interests” are mistaken.

Please see last year’s article, “The Sun Also Rises,” to explore other philosophical and theological puzzles that “form heterophroneo” finally puts to bed.

Explore “Durdle Dwarves” for yourself here. Press “Start” to see the world erupt chaotically but deterministically, according to a small set of rules.

Short and sharable:

A Musical Guide to How Morality Works

Until confronted with moral dilemmas, right decisionmaking — after we untangle our interests — seems pretty straightforward.

Like this guy. One happy fellow, playing his guitar:

And when we’re no longer “in dilemma,” we can forget about the complexity of morality, and revert to this “straightforward” / “common sense” / “plain to see” / “easy” falsity.

But it turns out that our moral practice is — roughly — a trio of three guitarists, all playing at the same time.

- Red is all about the rules. He represents moral stipulations that you’ve been taught, or that you’ve “red,” or what have you.

– - Green is all about seeking goals in service of all sorts of interests. But that’s not all; he’s also clumsy. Very clumsy. In the day-to-day, we’re rather inadequate at forecasting the innumerable consequences of each action we take. But, Green tries his darndest.

– - Blue is all about intuition; his feelings and gut-reactions to moral situations. His moral force is powered by direct appeals to conviction, disgust, anger, felt affection, etc.

A Beautiful Song…

For the most part, the three musicians play together very nicely.

Even if one musician rests while another plays, it sounds good.

Even if one musician plays a major and another its relative minor, it sounds pretty neat as a minor seventh.

… Usually

But sometimes, one musician plays a radically mismatched chord vs. the other two.

And it sounds terrible.

In other words, sometimes the gut and the clumsy goal-seeking go way against the rules. Sometimes the clumsy goal-seeking goes against both the rules and the gut. And sometimes the rules and clumsy goal-seeking are allied, but the gut dissents.

Judging the Musicians

So when one musician is out of sync, how do we figure out if he’s right to be out of sync?

To explore this question, let’s examine the three out-of-sync dilemmas in the abstract.

Red Out of Sync

This is when a common moral rule seems very counterproductive according to Green (clumsy goal-seeking) and Blue (gut intuition).

- Maybe Red is wrong. It may be that times, culture, or circumstances have changed so that the rule is no longer useful.

– - But maybe Red is right. It may be that the rule remains good, but the ways by which the rule is useful are very difficult to understand or untangle, and the gut and clumsy goal-seeking fail to ascertain them.

Green Out of Sync

This is when clumsy goal-seeking feels wrong and violates the common rules. The tension here is whether the person can be certain enough in his goal-driven analysis that he can say, “I’ve gotta do it anyway.”

- Maybe Green is wrong. The forecast was incorrect.

–

Example: You live in poverty and your family is very hungry. You see an opportunity to steal some groceries. You do not notice a plainclothes officer nearby, who will arrest you if you do; you will then be put in prison, and your family will be even worse off.

–

And this is just considering the interests of you and your family. Ideally our actions are in the best interests of our other relationships and even the world at large. Perhaps you won’t go to prison, but your theft will damage other people irreparably through unforeseen butterfly effects. And perhaps it may do damage to your own conscience, setting you on a dark path that ends in ruin.

–

You are not omniscient. You cannot know about every detail of your circumstances and what exhaustively will come of your actions. This is what makes your forecasting clumsy. The rules tell you not to steal, your feelings tell you not to steal, and even though your clumsy goal-seeking says to steal, you’d be best — here — to ignore it.

– - But maybe Green is right. The forecast, though clumsy, is indeed correct.

Blue Out of Sync

The rule says “do it,” the decision analysis says “do it,” but it feels wrong anyway; the gut says, “No, don’t!”

- Maybe Blue is wrong. The intuition is molded and crafted by experience, but that doesn’t make it impeccable — in fact, it’s largely driven by momentum and unconscious “preprogrammed” feelings of disgust, loss-aversive fear, righteous indignation, and even vengeance without fruitfulness. Good decisions can yet rub it the wrong way.

– - But maybe Blue is right. The rule is counterproductive (perhaps outdated, or should have been regarded as context-constrained) and the clumsy analysis was incorrect. Thankfully the intuition had been molded and crafted by experience to rebel against both the official rules and the incorrect analysis (clumsily performed).

The Common Denominator

Let’s simplify the above to answer our earlier question.

- When Red is out of sync, Red is right when the rule is useful (beneficial and constructive).

– - When Red is out of sync, Red is wrong when the rule isn’t useful (beneficial and constructive).

– - When Green is out of sync, Green is right when the analysis (albeit clumsy) is correct. (The analysis measured benefit and constructiveness.)

– - When Green is out of sync, Green is wrong when the analysis is incorrect. (The analysis measured benefit and constructiveness.)

– - When Blue is out of sync, Blue is right when the rule isn’t useful (beneficial and constructive) and the clumsy analysis (which measured benefit and constructiveness) was incorrect; thankfully, the intuition’s formative experience and other “preprogramming” raised warning flags.

– - When Blue is out of sync, Blue is wrong when the intuition’s limited formative experience and other “preprogramming” yields a gut-feeling contrary to usefulness (benefit and constructiveness).

See the pattern?

It’s consequence. Consequence is schematically “king.” We know this because it is the common judge against which all the musicians are measured.

- A rule is bad when it makes things worse.

– - A prospective analysis is bad when it through erroneous forecasting makes things worse.

– - One’s intuition is bad when it bends toward making things worse.

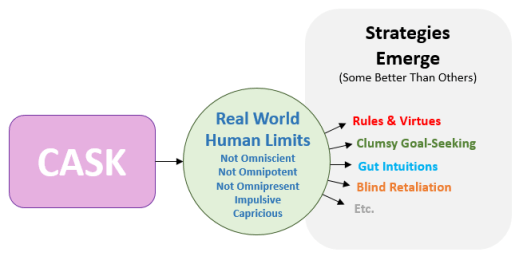

Let’s call “consequence as schematic ‘king'” CASK for short.

The Danger of Pure Consequentialism

As we’ve talked about several times, pure consequentialism can be dangerous. CASK can be true, but Green is still a clumsy analyzer.

We are not equipped for pure consequentialism; we are clumsy.

A practical adoption of pure consequentialism has us pitiful, clumsy humans deferring to Green every time, foolishly hoping that Green is a perfect “oracle” for CASK.

But as we’ve seen above, Green can be wrong.

Conflation of CASK and “always defer to Green” is a modal scope fallacy, and — tragically — fosters doubt in CASK.

The Danger of Deontology

But it’s also horrible to proclaim that the rules are schematically “king,” as if “Do this and not that” is the fabric of moral decisionmaking. It isn’t. Rather, rules are very useful ways of helping to guide us pitiful, clumsy humans to good decisions.

Rules are tools. And Red can be incorrect — or become incorrect over time, as circumstances change.

As Emergent Patterns

These strategies — rules, robust character guides called “virtues,” clumsy goal-seeking, and gut intuitions — emerge when CASK collides with the “real world” of human limitations.

When we recognize them as emergent from CASK — and not “more fundamental” than CASK — things make a whole lot more sense.

- Deontology, the idea that rules are the schematic “king” of meta-ethics, is misguided; rules emerge as useful under CASK.

–

It surprises us that Red and Green can “fight” so much, given this emergence. But it shouldn’t; this surprise is a product only of the aforementioned modal scope fallacy. Red and Green can fight all day; only the referee of true consequence — something to which we humans have limited access — can judge the winner.

– - Similarly, moral intuition is not the schematic “king” of meta-ethics. It likewise emerges from CASK, through both genetic and memetic evolutionary patterns.

–

It surprises us that Blue and Green can “fight” so much, given this emergence. But it shouldn’t. Blue is a bit “stuck in the past” due to how it’s made, and Green makes clumsy guesses about the future. It stands to reason they’d be prone to argument.

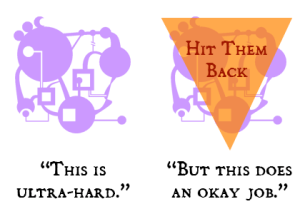

Retaliation as an Emergent Pattern

There are other patterns that emerge as well.

One of the biggest relates to justified moral reaction.

Under CASK, a justified moral reaction (to some bad thing) ideally has three missions: Repairing the situation, repairing the person, and repairing the institution.

- The situation was such that the transgressor was free to transgress and hurt others. Attempt to repair that situation by restricting that person.

– - The person needs to learn — convincingly — not to transgress anymore. Attempt to repair the person by whatever means are most feasible and practical.

– - Society as an institution seems to be producing people who behave this way. Attempt to repair the institution by going after institutional cofactors, like domestic abuse, poverty, and lack of education and mentoring guidance. (One very common play at institutional repair is to overpunish people for its deterring effect… but we’d hope to find a better way.)

It goes without saying that if all of these missions were “easy” for us, we’d do them with every transgressor, and with no rational hesitation.

But they aren’t easy for us. They’re really hard.

And thousands of years ago, they were even harder.

- It’s not easy to restrict a person when you have no secure prisons and a lack of sufficient infrastructure to sustain prisoners indefinitely and humanely.